In 1991 Bill Gates' Corbis promised the Guggenheim a spiffy collection management database if we only gave them the exclusive rights to our images. Thank god I was able to sink that idea.

At about the same time, MOMA tried to get my dad and the other founders of New York's artist-run Tanager Gallery to donate their archives. The Tanager artists chose the Smithsonian instead, hoping for broader public access. Judging from the

following article, that may have been a mistake.

Wave cash and shiny tech in front of a nonprofit, and watch them drop their values and hold out their hands. If power corrupts, I suspect centralized power corrupts absolutely.

--jon

April 1, 2006

Smithsonian Agreement Angers Filmmakers

http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F5071FFB39540C728CDDAD0894DE404482

By EDWARD WYATT

Some of the biggest names in documentary filmmaking have denounced a recent agreement between the Smithsonian Institution and Showtime Networks Inc. that they say restricts makers of films and television shows using Smithsonian materials from

offering their work to public television or other non-Showtime broadcast outlets.

Ken Burns, whose documentaries "The Civil War" and "Baseball" have become classics of the form, said in an interview yesterday that he believed that such an arrangement would have prohibited him from making some of his recent works, like the musical

history "Jazz," available to public television because they relied heavily on Smithsonian collections and curators.

"I find this deal terrifying," Mr. Burns said in a telephone interview from San Francisco, where he is filming interviews for a documentary on the history of the national parks. "It feels like the Smithsonian has essentially optioned America's attic

to one company, and to have access to that attic, we would have to be signed off with, and perhaps co-opted by, that entity."

On March 9, Showtime and the Smithsonian announced the creation of Smithsonian Networks, a joint venture to develop television programming. Under the agreement, the joint venture has the right of first refusal to commercial documentaries that rely

heavily on Smithsonian collections or staff. Those works would first have to be offered to Smithsonian on Demand, the cable channel that is expected to be the venture's first programming service.

A Smithsonian official who is managing the institution's content and production assistance for the venture said yesterday that while the new arrangement did limit the ability of commercial filmmakers to sell some projects elsewhere, it ultimately

would affect a small number of the works that draw on the museum's resources.

"It's not our obligation to help independent filmmakers sell their wares to commercial broadcast and cable networks," said the official, Jeanny Kim, a vice president for media services for Smithsonian Business Ventures.

"What it boiled down to is that we don't have the financial resources, the expertise or the production capabilities," she added, to continue to provide extensive access to materials but not to reap any financial benefit from the result.

She said films that made incidental use of a single interview with a staff member or a few minutes of pictures of elements of the Smithsonian collections would be allowed.

The Showtime venture, under which the Smithsonian would earn payments from cable operators that offered the on-demand service to subscribers, comes as the Smithsonian has suffered financial problems. At a Congressional hearing on Wednesday, a

Smithsonian official said some necessary repairs to Smithsonian buildings could not be made because of lack of financing. That led to a suggestion by Representative James P. Moran, Democrat of Virginia, to suggest that the institution should charge

admission, a proposal that its board of regents has rejected repeatedly.

The Showtime agreement began attracting widespread attention this week as filmmakers said they had been told that some of their projects might fall under the agreement. Two Smithsonian curators, who were granted anonymity because they feared for

their jobs if they spoke publicly about the Showtime venture, said in interviews yesterday that they could not be certain what kind of projects would be subject to the restrictions because details of the contract with Showtime had been shared with

few employees below the executive level.

Linda St. Thomas, a Smithsonian spokeswoman, said the details of the contract with Showtime were confidential and would not be released publicly. She said the outlines of the agreement had been left deliberately vague to allow the Smithsonian to

consider "on a case-by-case basis" whether a proposed project competes with its new television venture or not. A Showtime executive, Tom Hayden, said the deal was not intended to be exclusionary but was intended to provide filmmakers with an

attractive platform for their work.

One well-known filmmaker, Laurie Kahn-Leavitt, said she had been told recently by a Smithsonian staff member that her last film, "Tupperware!," a history of the creation and marketing of the venerable food-storage containers, would have fallen under

the arrangement, because much of the history of Tupperware is housed at the Smithsonian. The documentary, which won a Peabody Award in 2004, was broadcast on "American Experience," the PBS show produced by WGBH, the Boston public television station.

"This is a public archive," Ms. Kahn-Leavitt said. "This should not be offered on an exclusive basis to anyone, and it's not good enough that they can decide on a case-by-case basis what they will and won't approve."

Margaret Drain, a vice president for national programs at WGBH, said she feared that public television programs like "Nova" and "American Experience" would suffer greatly because of the new restrictions.

"These are programs that regularly rely on the collections of the Smithsonian Institution," she said. "If access is restricted, we are really going to be in trouble."

She added: "I'm outraged that a public institution would do a semiexclusive deal with a commercial broadcaster."

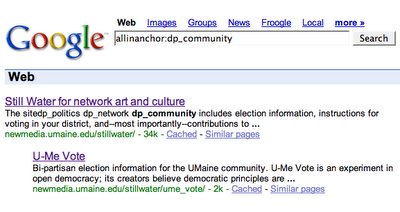

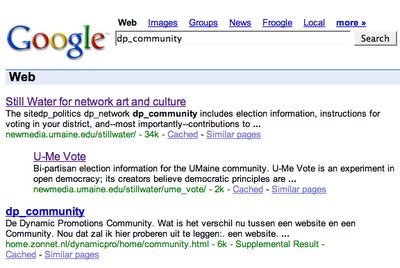

When I used this same technique to embed a tag called "dp_community", the site I linked to appeared but also the page that did the linking. (See figure 2.) At first I was confused by this, because although GoogleBot seems to harvest hidden text, PageRank tends to omit it from search returns--because it can be used by spammers to direct people searching for "car" to porn sites, etc.

When I used this same technique to embed a tag called "dp_community", the site I linked to appeared but also the page that did the linking. (See figure 2.) At first I was confused by this, because although GoogleBot seems to harvest hidden text, PageRank tends to omit it from search returns--because it can be used by spammers to direct people searching for "car" to porn sites, etc.